The United States stands apart when it comes to firearms. No other country, even those in the throes of war, has more civilian guns than citizens. Given the many known hazards associated with guns, including being the leading cause of death for children and teens in America, one overlooked danger is the ammunition itself, the vast bulk of which is made of lead.

Pulling the trigger of a firearm releases a plume of lead dust, which can be inhaled. Spend a few hours hunting or in a firing range, and lead will cling to your skin, clothing and personal belongings. The toxic metal, harmful to humans and animals, can be tracked into your car and home, contaminating car upholstery, furniture and carpeting. If you visit a firing range often, you run the risk of repeatedly harming yourself and your family.

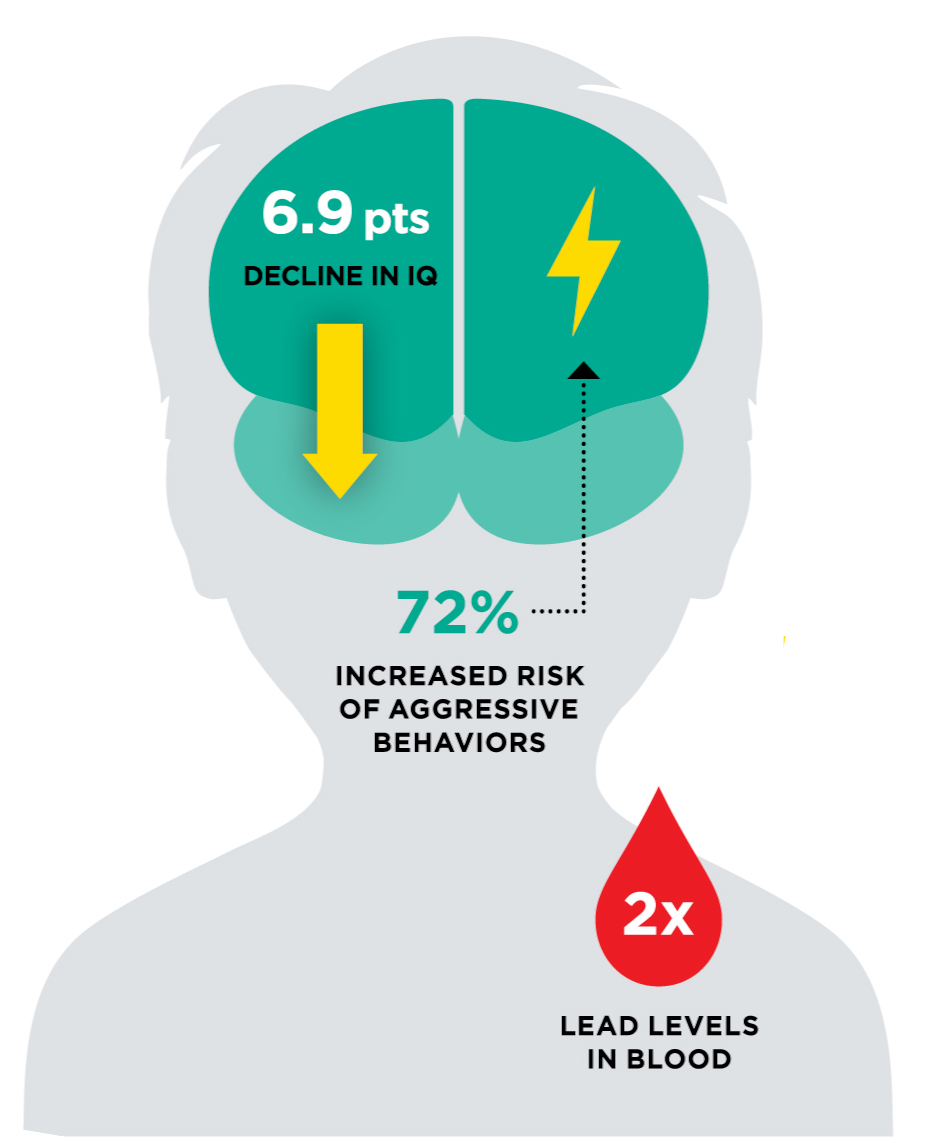

Exposure to lead can have lifelong effects. Children are especially vulnerable as the toxin negatively impacts their neurological development, leading to a host of physical, behavioral and emotional issues, including learning disorders, anemia and hyperactivity. Joseph Braun, professor of epidemiology and director of the Center for Children’s Environmental Health in Brown’s School of Public Health, explains that a doubling of blood lead levels is associated with a 72% increased risk of aggressive behaviors. “Lead poisoning also results in a 6.9 point decline in IQ,” he said, “and it’s estimated that each IQ point is worth a loss of $17,000 in lifetime earnings.”

Great strides have been made since the 1970s to reduce lead from our environment. The elimination of leaded gasoline and the restriction or outright banning of lead paint were the chief drivers that had lowered the blood lead levels of Americans by more than 75 percent by the 1990s.

Yet lead persists. Polluted air and water are often to blame. Older housing stock, with legacy pipes and paint, are a high concern; and tainted consumer products like food, cosmetics, toys, cookware and ceramics make the news. Less well known, are the dangers posed by guns and lead ammunition.

A Lightbulb Moment

Christian Hoover, now a Ph.D. student studying epidemiology at Brown and an investigator at the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, was working as a project manager in environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health studying lead deposits in bones and teeth, and their risks related to Alzheimer’s and dementia, when he noticed a recurring theme. While conducting interviews with Veterans in a geriatric center, Hoover heard many of the Veterans mention gun use when discussing potential exposures to lead.

In 2018, it struck him “like a bolt of lightning” that there could be a significant connection between firearm ownership and lead exposure, especially in family members of gun owners. This revelation shifted his perspective on injury prevention and lead poisoning. Since then, Hoover has led multiple groundbreaking studies on the relationship between firearm ownership and blood lead levels in children and adults, as well as the correlation between firearm-related lead exposure and suicide.

Trouble in the Bay State

In 2023, Hoover conducted a study that focused on lead exposure in the 351 cities and towns of Massachusetts. Analyzing data at the sub-county level, the team divided all of the cities and townships into four categories based on gun ownership levels. They looked at townships that had the most civilian guns, like Oxford and Peru, and compared them to towns with the fewest, like Cambridge and Newton. They examined lead levels within these quartiles, while controlling for other major sources of lead exposure.

By removing the impact of known lead sources—such as lead in water, occupational exposures, air pollution and residential lead dust from older housing stock—they were able to isolate the relationship between gun ownership and lead exposure.

The results were striking and clear: Hoover and his team found that lead from firearms is one of the most significant sources of elevated child blood lead levels in the state. As the proportion of homes with guns increased, the study found, so did lead levels. This pattern persisted even when accounting for all other significant exposure sources, indicating a strong association between gun ownership and child lead exposure.

A Nationwide Pattern

Hoover’s 2024 study, co-led by Braun, expanded upon his previous work by investigating the issue on a national scale. The study’s results are consistent with Hoover’s earlier findings: Firearm ownership is a predictor of lead exposure, and was found to be positively correlated with elevated lead levels in children in 44 U.S. states. Even after controlling for the age of housing, water quality and parental occupation, gun ownership remained a significant associated factor.