In 2024 Steward Health Care filed for bankruptcy, depriving socioeconomically disadvantaged communities of essential health services, straining nearby state hospitals and leaving more than 4,430 health providers, staff and administrators out of a job.

Steward, formerly the Caritas Christi Health Care System, was once the second-largest health care system in New England, employing over 12,000 people and serving more than one million patients each year—largely from poor and working-class communities.

A nonprofit system of six Catholic hospitals in cities like Brockton, Dorchester and Fall River, Caritas was acquired in 2010 by the private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management. Cerberus, which takes its name from the mythical three-headed dog that guards the gates of the underworld, converted Caritas into a for-profit system and rebranded it as Steward Health Care.

Just one year after a legally binding review period designed to prevent predatory facility closures or sales, Cerberus offloaded the hospital system’s most valuable asset: its real estate. The sales generated significant profits for Cerberus investors, Steward’s CEO and its leadership team.

This is not a new approach. The transaction followed a common private equity strategy known as a sale-leaseback, where firms sell off health care properties to a real estate investment trust—or REIT—for quick profits. In this case, the REIT, Medical Properties Trust, purchased the buildings and leased them back to the hospitals at unsustainable costs.

As a result, the hospitals that had owned their buildings for at least 35 years, struggled to cover their rent. They were forced to cut back on staffing, supplies, equipment and care, putting patients at risk and increasing mortality rates for certain conditions.

Cerberus sold its controlling stake in the hospital system to Steward in 2020, making nearly $800 million in the sale—more than four times its original investment.

The Rise of Private Equity

Acquisitions of health care facilities by private equity (PE) firms, like Cerberus’ takeover of Caritas, have risen dramatically over the past 20 years, and are continuing at an alarming rate. Researchers from the School of Public Health’s Center for Advancing Health Policy through Research (CAHPR) write that from 2000 to 2018 “PE capital investment in the health care industry grew by more than 2000%, skyrocketing from $5 billion to $100 billion, leading to an estimated $1 trillion spent in PE investment activity in health care over the past decade.”

Private equity firms operate by pooling money from investors—including wealthy individuals, sovereign wealth funds, university endowments and pension funds—and use that capital, along with a small portion of their own, to borrow additional funds.

“Typically, PE firms only put in 20 to 30% of their own money and borrow the rest—meaning the company they acquire, like a hospital system, is the one that carries the debt,” said Erin Fuse Brown, director of CAHPR’s Health Policy and Law Lab and professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown. “The hospital’s future revenue, land and other assets become collateral for this debt.”

The goal of PE firms, Fuse Brown said, is to flip the company within three to seven years for a profit. “They aren’t looking to improve operations for the long haul; they want quick, high returns.”

And the returns are high here. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, health care spending in the United States reached $4.9 trillion in 2023, accounting for 17.6% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product.

PE firms began to focus on the lucrative health care market in the 1990s, starting with acquisitions of hospitals and nursing facilities. They then expanded their operations to include all manner of health care entities from hospice and telehealth services to opioid treatment programs. Over the past ten years, PE has aggressively turned its attention to physician practices, particularly in the fields of primary care, cardiology, behavioral health, dermatology, ophthalmology, gastroenterology, radiology, anesthesiology and emergency medicine.

The upshot is that PE firms now own more than half of all medical practices in some regions of the U.S. They oversee nearly a third of staffing in U.S. emergency departments. They own more than 450 hospitals.

In the behavioral health sector alone, PE firms acquired more than 5,000 facilities in all 50 states between 2010 and 2022, according to a recent study led by Yashaswini Singh, assistant professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown. And the pace is accelerating, with 56.2% of all PE acquisitions of behavioral health practices taking place during or after 2020.

“PE firms have invested in and are profiting from mental health services, addiction treatment services and even eating disorder treatment and autism services,” Singh said. “In general, PE investments in health care reveal the fundamental tension between financial firms’ obligations to investors and clinicians’ obligations to patients. And while every investment is different, research has shown that PE acquisitions consolidate ownership of health care entities under financial firms without generating tangible benefits for patients or health care workers.”

Market Power

Proponents of vertical consolidation—where entities higher in the supply chain, such as insurers, acquire physician practices and pharmacies—argue that consolidation is beneficial to the patient; that it coordinates patient care, provides more touchpoints with providers and pharmacies and allows for a more seamless transition between insurer, doctor and pharmacy. In a word, efficiency.

But the trend has led to a highly concentrated market dominated by a few large health systems and insurers. Today, just two companies—CVS/Aetna and the UnitedHealth Group—control 27% of the United States health care market.

UnitedHealth’s total yearly revenue outstrips many of the nation’s largest companies, including Berkshire Hathaway, Alphabet and Microsoft. It is the fourth-largest company of any type by revenue in the U.S., just behind Apple. It owns the largest claims-processing company, holds the largest portion of enrollment in the Medicare Advantage program and employs more physicians than any major clinic chain or hospital system in the nation.

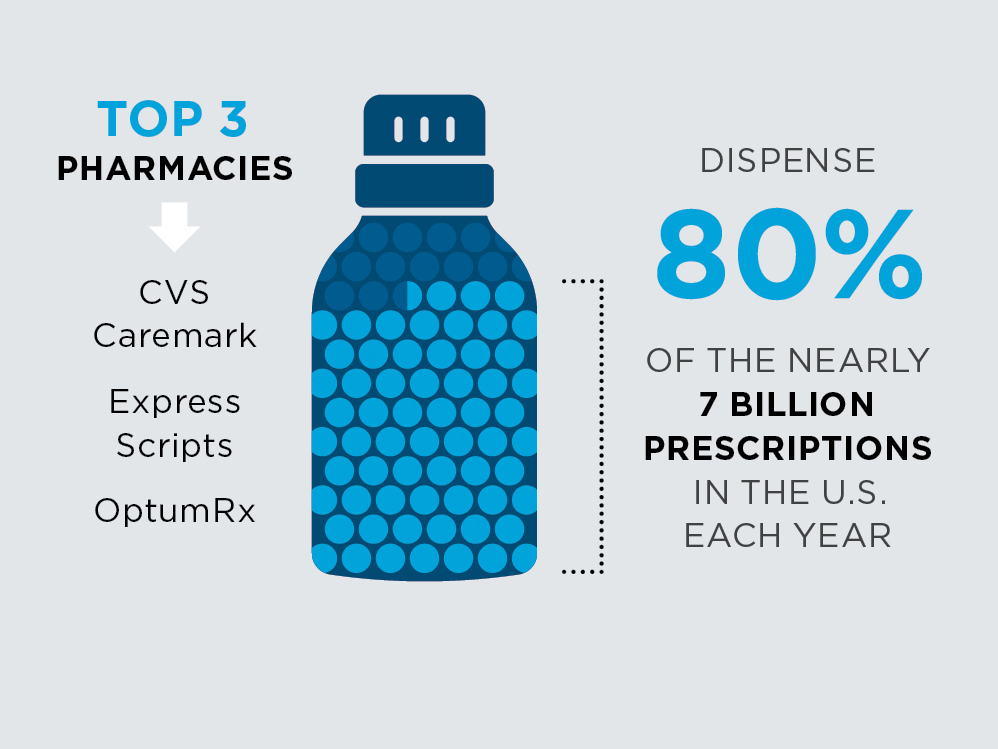

Meanwhile, CVS Caremark, Express Scripts and OptumRx—the nation’s top three pharmacy benefit managers—handle about 80% of the nearly 7 billion prescriptions dispensed by U.S. pharmacies each year. OptumRx is owned by the UnitedHealth Group. CVS and Express Scripts merged with Aetna and Cigna in 2018, respectively.

“Health care consolidation—like consolidation in any market—happens when ownership and control become concentrated in fewer and fewer hands,” Fuse Brown said. “At the extreme end, you get a monopoly, where a single company dominates a market—with just one health insurer or hospital system in a given region. But even without full monopolies, you still see markets where only one or two major players control most of the industry.”

How Did We Get Here?

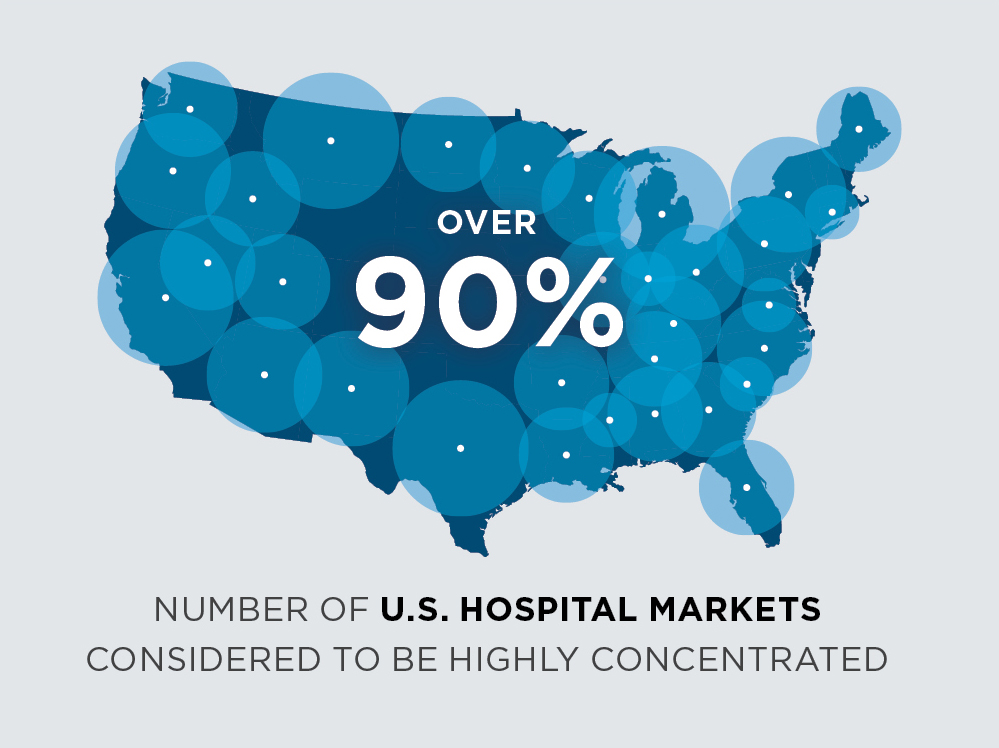

One of the earlier drivers of consolidation was a loosening of the regulatory environment during the 1990s. This led to the first wave of hospitable mergers, “which eventually resulted in the formation of large, multi-state health systems,” Brown University researchers write. Today, “over 90% of U.S. hospital markets are considered to be highly concentrated.”

Other factors include Medicare’s shift, in 1997, from a fee-for-service model to a capitation-based, per-beneficiary payment system under the Medicare Advantage program. This inspired insurance companies to purchase physician practices and, often times, to exaggerate patient diagnoses to accrue greater profit. This maneuver is called “upcoding.” In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act placed limits on the amount of profit insurers could make on health insurance, companies branched into other lines of the industry where profits remain uncapped.

times, to exaggerate patient diagnoses to accrue greater profit. This maneuver is called “upcoding.” In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act placed limits on the amount of profit insurers could make on health insurance, companies branched into other lines of the industry where profits remain uncapped.

The irony is that these efforts by federal policymakers were meant to curb profiteering and lower costs in this sector; instead, they inspired greater acquisitions of physician practices and other types of provider systems. And once the process began, it took on a life of its own.

“One of the biggest reasons for health care consolidation is that as the market becomes more consolidated, it becomes harder for smaller, independent providers to compete,” Fuse Brown explained. “If a dominant hospital system or physician network takes over a region, smaller players often feel they have no choice but to merge or get acquired just to survive.”

Ultimately, consolidation is about gaining ever-greater market power and consequently greater leverage to negotiate higher prices with insurers. “In markets without strict price regulations, the bigger you are, the more essential you become to an insurance network,” Fuse Brown said,

“so insurers are forced to accept your higher rates.”

The Cost of Consolidation

Fuse Brown explains that across all types of consolidation—whether it’s hospitals merging with hospitals, hospitals acquiring physician groups or PE firms and insurers acquiring health care entities—the result is always the same: higher costs for patients and taxpayers, often by double-digit percentages (20-40%).

Quality of care is also at risk.

“While industry leaders often claim that consolidation improves efficiency and care coordination, studies show little to no improvement in quality and, in some cases, quality even declines,” Fuse Brown said. “When there’s competition, hospitals and health care systems have to work harder to attract patients, which can drive improvements in quality and cost. In contrast, when a few big players dominate a market, there’s less incentive to innovate or maintain high standards.”