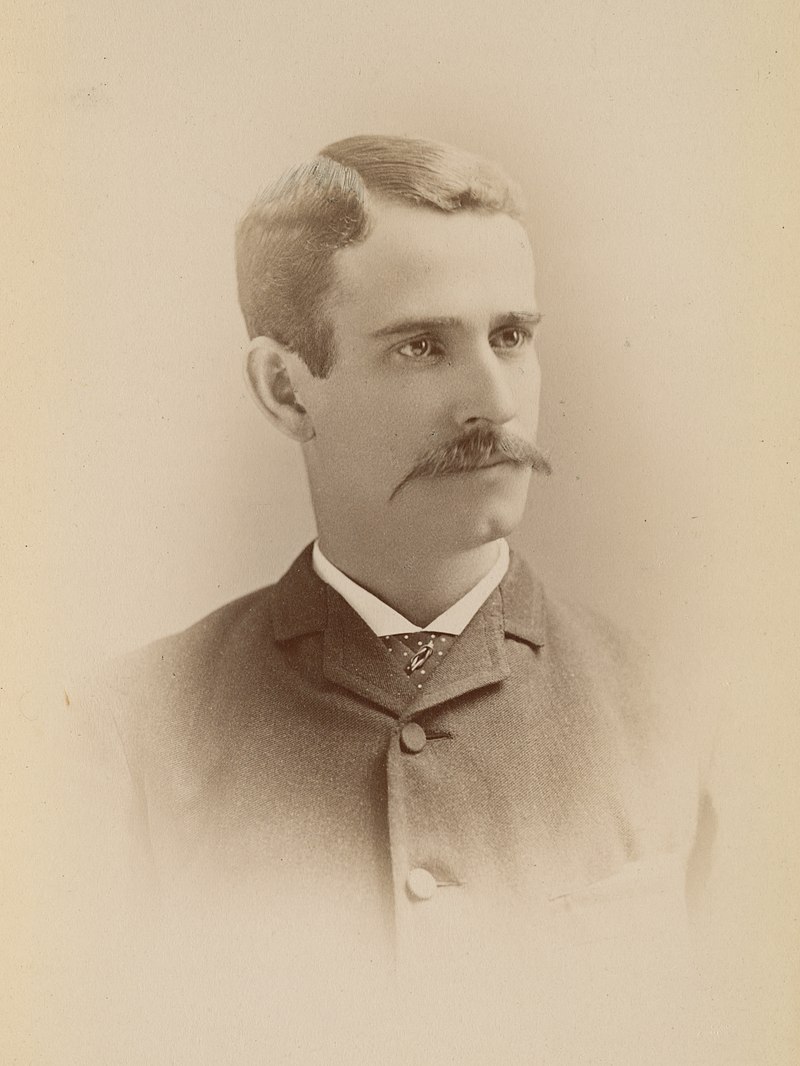

In 1884, only a few years after graduating from Brown, Charles Value Chapin returned to his Providence hometown to become the city’s second Superintendent of Health. An early proponent of the newly-emerging germ theory of disease, Chapin was a pioneer in a new era of public health practitioners, and shared his insights in lectures on physiology at Brown. During deadly outbreaks of cholera and smallpox, he went from home to home in Providence to understand how these diseases were spreading through the community. Informed by his emerging insights about the dynamics of infection, Chapin established one of the nation’s earliest municipal public health laboratories.

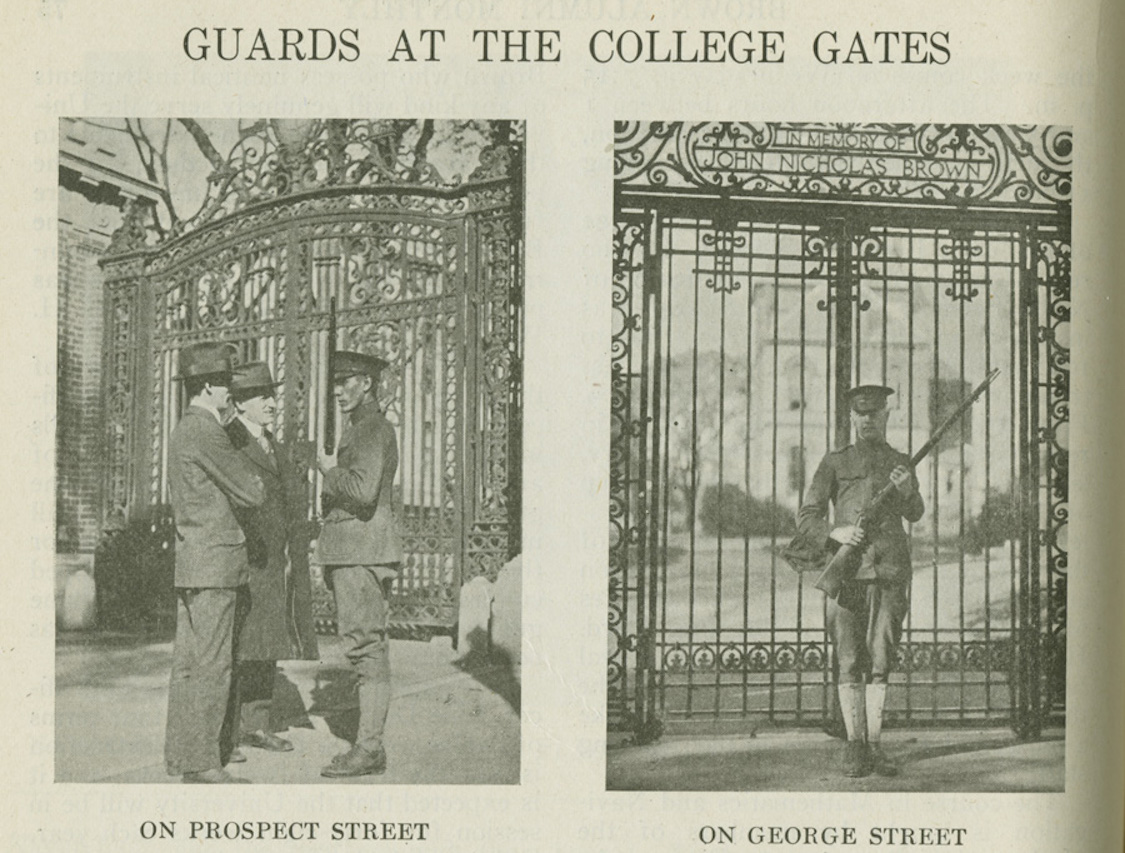

The city’s response to the 1918 influenza proved to be Chapin’s greatest challenge. The epidemic struck Providence early, as American soldiers began disembarking at its port in the wake of the First World War. Chapin understood that the pathogen had spread so widely that controlling it would be extremely difficult, and compulsory infection control measures would pose their own health threats. Drawing on his scientific understanding of epidemiology, Chapin opposed the broad lockdown ordered by the state Board of Health, believing it came too late to slow the pandemic.

Chapin wrote “The children, if turned out of school, will mingle on the streets. People turned out of churches or other places will mingle just the same all other days of the week, in streetcars, factories or places of business. They will mingle in the stores.” Chapin knew that fighting influenza would require public participation, and worried that overly broad, compulsory measures would turn the Providence community against public health efforts. The governor postponed the lockdown.

Instead, Chapin asked physicians in Providence to notify him of cases of influenza, which they were not otherwise required to report, and prepared for the rising tide of illness. He recruited nurses to care for the growing number of patients he knew would be coming. He issued public health advisories asking sick people to stay home. Under his guidance, which was based on close observation and engagement with the Providence community, the city navigated the remainder of the influenza pandemic with relative success—the city of Philadelphia had a death rate more than four times that of Providence.

The Department of Community Health

For 40 years after the Great Influenza, however, public health was largely overlooked at Brown. But in 1960, Brown University President Barnaby Keeney began the process of reinstating the University’s medical school, working together with the Rhode Island Hospital. Just a few years after the first cohort of Brown students were awarded their Masters of Medical Sciences, the University created the Department of Community Health in 1972.

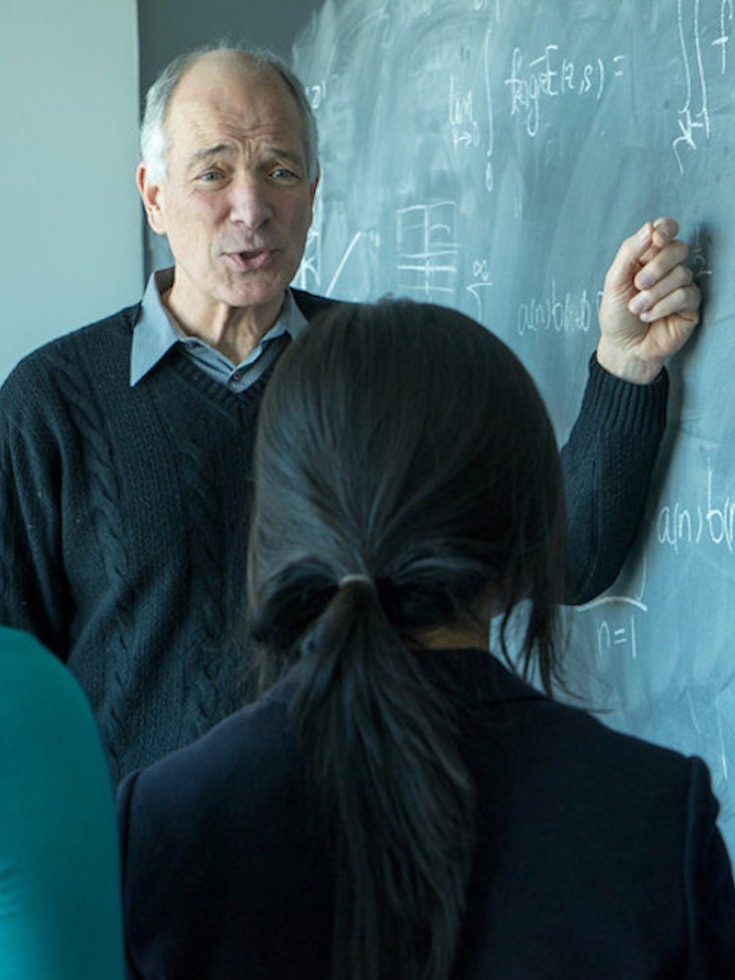

Vincent Mor joined the department in 1981, and began gathering data to assess hospice care, a new, community focused model of care for the terminally ill. “In the early ‘80s and ‘90s, we didn’t think in terms of public health so much,” Mor said, “we thought in terms of clinical medicine. But as time went on, because of both the research and the people we were recruiting, we were more and more drawn to this population perspective that is public health.”