Newly released data from the Association of American Medical Colleges shows a double-digit drop in the enrollment of Black, Hispanic and Native American students in medical schools, a trend that follows the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision to ban the consideration of race in admissions. This decline deepens an already significant structural disparity in the U.S., where Black and Hispanic physicians represent just 5% and 6% of the medical workforce, respectively.

How does this disparity impact health care quality? Research shows that patients are more likely to follow medical recommendations when their providers share similar personal and cultural backgrounds. Diversity also improves patient satisfaction, trust and communication between patient and provider, while encouraging broader perspectives in medical research. Importantly, racially diverse doctors are more likely to work in underserved communities, providing care to uninsured individuals and Medicaid beneficiaries. When providers do not mirror their patient populations, these outcomes are less likely to occur.

A team of researchers from the Brown University School of Public Health has published a study examining an additional barrier to receiving care from racially or ethnically concordant physicians: Medicare Advantage (MA)—the privately run segment of Medicare that enrolls Black and Hispanic patients at disproportionately higher rates—and the restrictions it often places on the network of available providers.

Led by David Meyers, associate director of Brown’s Center for Advancing Health Policy through Research and assistant professor of health services, policy and practice, and Dr. Amal Trivedi, professor of health services, policy and practice and of medicine at Brown, the team evaluated the availability of Black and Hispanic primary care physicians for MA enrollees and compared it to the broader pool of physicians practicing in the same counties. Their emphasis on primary care is rooted in strong evidence showing that Black patients who receive primary care from Black physicians are more likely to access critical preventive services.

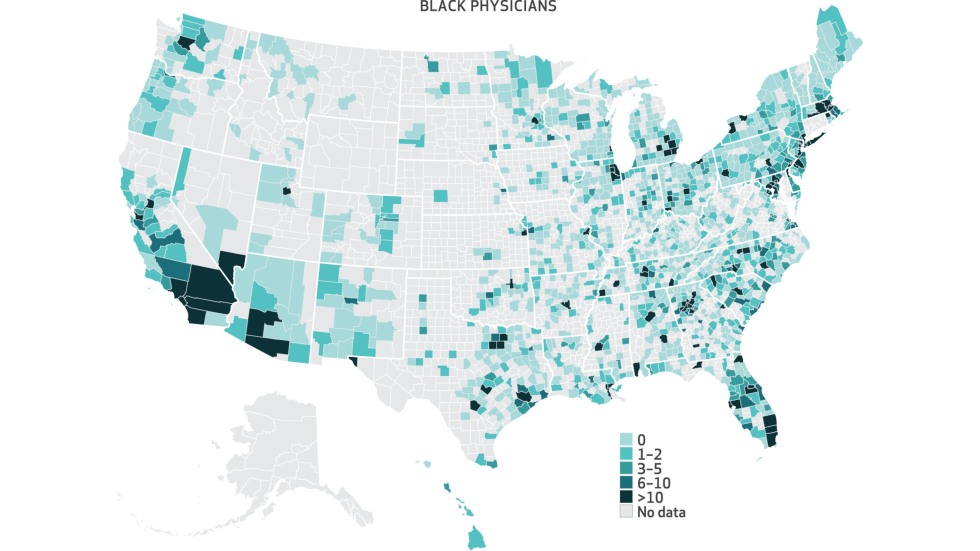

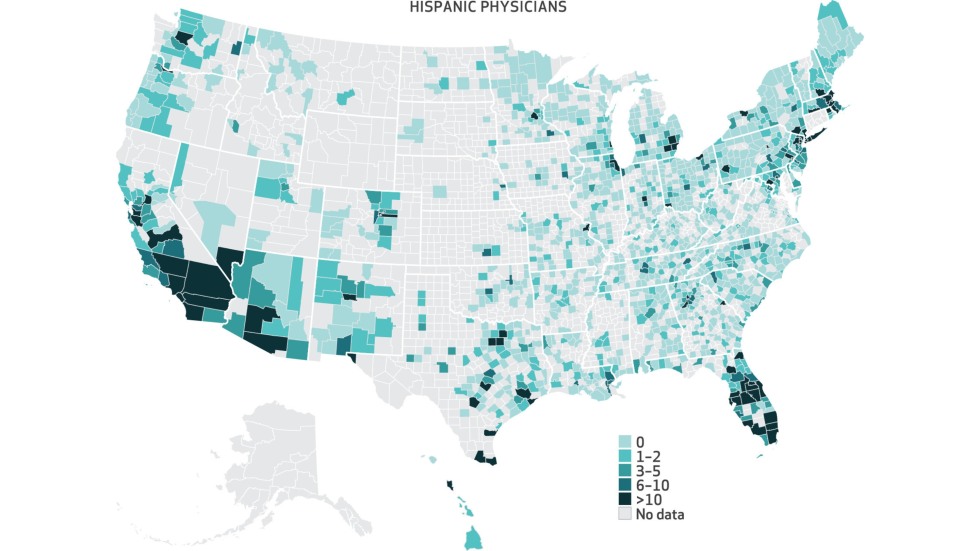

Here’s what they found: One in five Black and Hispanic individuals in Medicare Advantage plans had no access to Black or Hispanic doctors in their network. Roughly four out of ten counties lacked Black doctors in Medicare Advantage networks, and nearly half of all counties had no Hispanic doctors available. MA plans also included a smaller percentage of Black and Hispanic physicians compared to white physicians.

“Medicare Advantage plans often limit provider networks, which may restrict access to racially or ethnically concordant physicians, and that is essentially what we found in this study,” said Trivedi. “While 51% of white physicians in a given Medicare Advantage enrollee's county were included in the MA network, the inclusion rates were lower for Black and Hispanic physicians. Specifically, only 43% of Black physicians and 44% of Hispanic physicians practicing in the same counties were included.”