In 1912, the German pharmaceutical company Merck developed 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or MDMA, in an effort to create a drug that would induce blood clotting and rival a coagulant medicine by Merck’s competitor, Bayer. Coagulants are especially helpful in the fields of emergency and military medicine, used to treat hemorrhages and avert blood loss, saving lives. But Merck’s project was ultimately abandoned, and MDMA remained largely forgotten until the late 1970s. It was then that medicinal chemist Alexander Shulgin began promoting the drug as an adjunct to psychotherapy.

By the 1980s, MDMA’s therapeutic potential was overshadowed by the stigma of its recreational use. It had become popular at clubs, and its reputation as a party drug—commonly called Ecstasy or Molly—led to its criminalization in the U.S. in 1985.

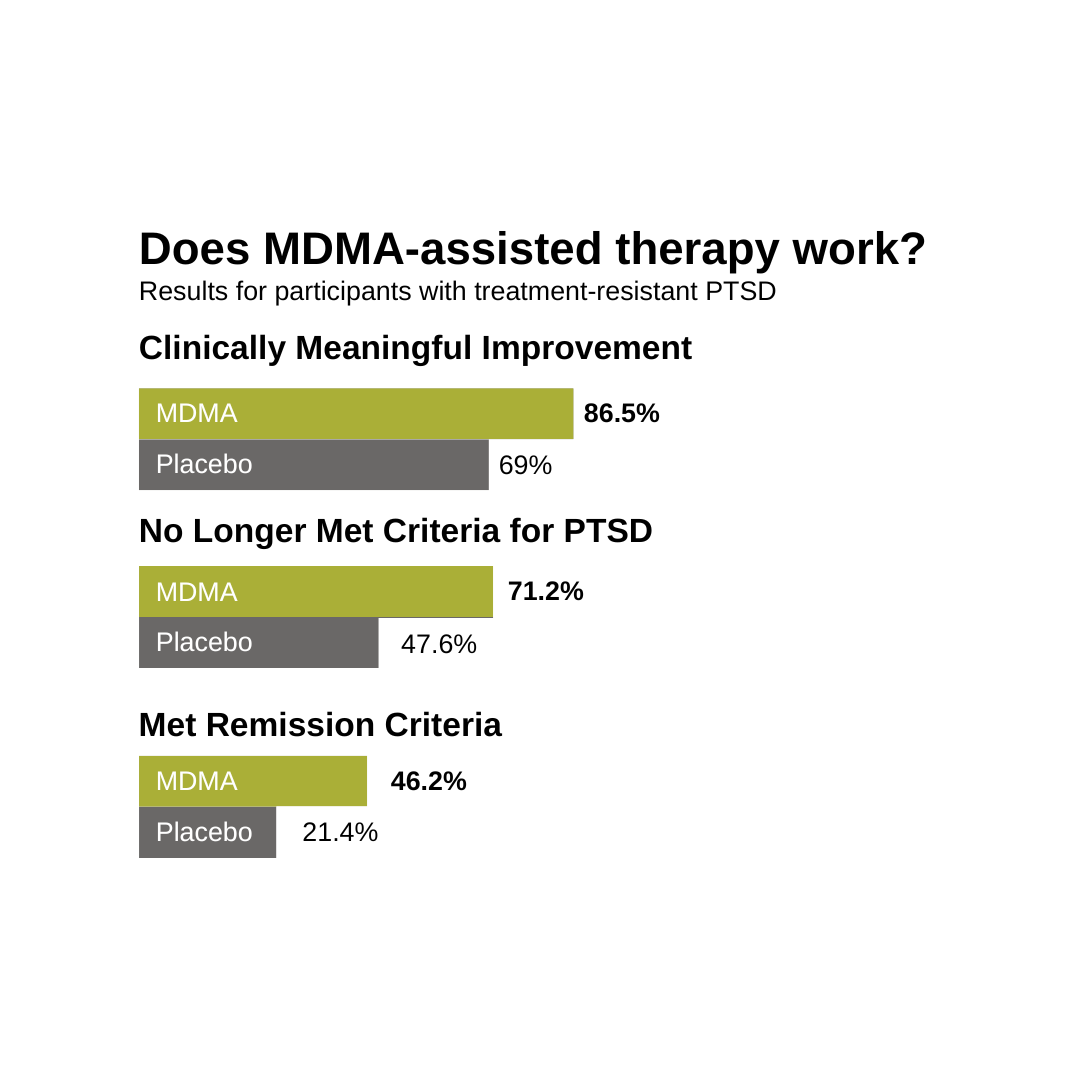

But in recent years, researchers have reevaluated MDMA, especially in combination with clinical therapy, as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). There are only two medications—the antidepressants Zoloft and Paxil—currently prescribed to treat PTSD, and the FDA has not approved a new drug to treat the disorder in over two decades.

Although the results vary, multiple studies have shown that PTSD is linked to a significantly increased risk of suicide among Veterans, with rates being at least several times higher than those without PTSD. The risk is particularly pronounced among female Veterans.

Recognizing MDMA’s potential to save lives, the FDA granted breakthrough therapy status to MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in 2017 to accelerate the treatment’s development. And the Veterans advocacy group Heroic Hearts Project has expressed its passionate support for this novel treatment.

Still, the approval process has not been easy. Researchers have recently met resistance from an advisory committee for the FDA, posing new challenges for the advancement of a potentially life-saving intervention.

Why Veterans?

Three intrepid Brown faculty members—Carolina Haass-Koffler, associate professor of behavioral and social sciences and of psychiatry and human behavior, Erica Eaton, assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior and of behavioral and social sciences and Christy Capone, assistant professor of behavioral and social sciences and of psychiatry and human behavior—have stepped into the breach to study MDMA-assisted therapy for Veterans with co-occurring PTSD and alcohol use disorder (AUD). All three researchers are affiliated with the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies at Brown.

Their study is the first of its kind, and last summer, the team achieved a milestone by enrolling 12 participants and beginning treatment with their first patient.

In terms of psychotherapy, “there are some evidence-based treatments that work well for some patients, but are also accompanied by high drop-out rates,” Capone said. “But for Veterans who suffer severe symptoms, these approaches do not work very well, and we’ve seen firsthand that they aren’t getting the relief that one might hope.”

For Capone and Eaton, who counsel Veterans with PTSD and AUD at the Providence VA Medical Center, the situation is dire.