Early August in his office at the Brown School of Public Health, Will Goedel was running vaccine numbers through a mathematical model and plotting them on a map. The maps, when complete, would help demonstrate where monkeypox vaccines were most needed, and how the country’s limited supplies could be used most effectively. He sighed at the paucity of data, and the challenge of matching the need for testing to vaccine supply.

There was a sense of déjà vu to the work. Monkeypox is the second epidemic of his young career as an assistant professor of epidemiology, and he couldn’t help wondering how the country had reached this stage again, and so quickly on the heels of COVID.

One evening also in early August, Goedel’s colleague in the School of Public Health, Amy Nunn, was ordering a drink at a gay bar in Providence. But she wasn’t at the bar to let off steam, she was conducting messaging research on monkeypox. The clinic she directs, Open Door Health, which serves the LGBTQ+ community in Providence, was about to launch a monkeypox campaign and she wanted to make sure the prevention message was on point.

Goedel and Nunn, professor of behavioral and social sciences and of medicine, embody an emerging sort of academic, trained as Ph.D.s but steeped in the public health realities of America. This new crop of academics has seen the carnage brought by years of health disparities, tragically played out during the COVID pandemic and now monkeypox. They view research not as an end in itself, but as a tool that should be used in the service of social change. While academia has historically moved slowly and methodically, these two health emergencies have challenged the way many view research and the inner workings of academia.

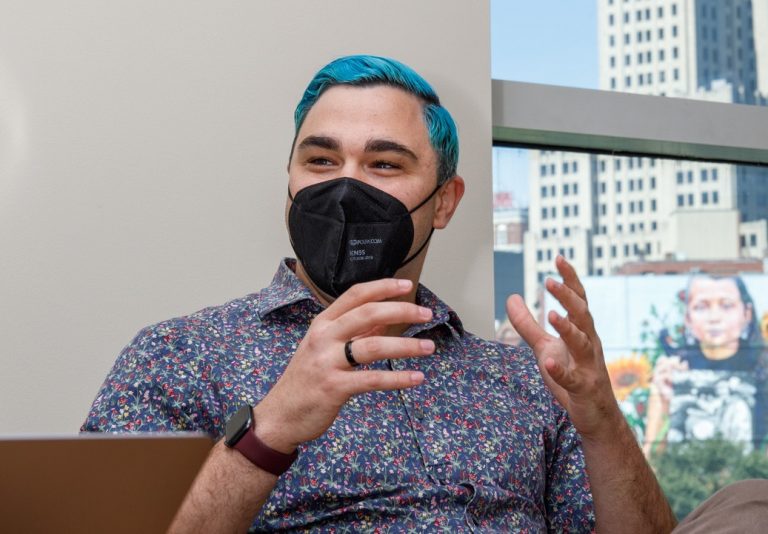

Goedel, who defended his dissertation over Zoom from his kitchen in March 2020, has spent his entire career as a professor responding to public health crises. “When COVID hit,” he says, “I realized quickly that I needed to roll up my sleeves, and I couldn’t roll them back down. There is no going back.”