Starting Out

Nunn grew up in Arkansas and after graduating from college, was a Fulbright Fellow, of which there are only 800 in the U.S. a year. She started her professional life in politics: in 2001, she became the Hispanic Outreach Coordinator for Arkansas Sen. Blanche Lincoln.

After finishing her MS and ScD in global health at the Harvard School of Public Health, she completed her post-doctoral fellowship at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School.

When Nunn considered the best route to tackling public health problems, particularly the high rates of HIV in Black urban communities, she thought back to her time in Sen. Lincoln’s office. While her primary job was working with the Hispanic community, she also got to know Black residents, and made connections with Black churches and Black pastors.

“If you want to get something going with the Black community, you often work with churches. I learned how to do that when I worked for a U.S. Senator,” she said.

The U.S. sees nearly 38,000 new HIV infections a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While that may look small on a national scale, and encouraging since the rate of infection has dropped more than two thirds since the height of the epidemic in the mid-1980s, HIV infection rates in some urban neighborhoods are higher than in many Sub-Saharan African countries. Since 2014, the overall U.S. HIV infection rate dropped to 13.3 per 100,000 people but remained stubbornly high and flat for Black Americans at 45.4 per 100,000.

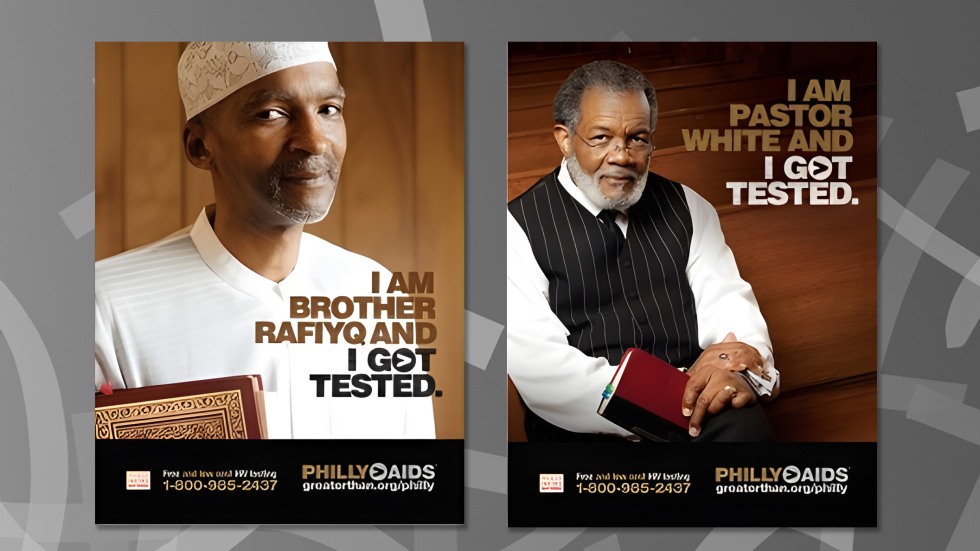

Testing resistance is part of the problem for Black gay and bi-sexual men, rooted in stigma, homophobia and discrimination, which had historically been perpetuated by churches. This may mean it’s difficult for some men to be open about their sexuality and therefore see themselves as someone who is at high risk for HIV and should be tested regularly.

Gay and bisexual Black men of all ages also face economic barriers to getting medical care, creating a situation where they may be unknowingly infected and not receiving treatment. They also may not have access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a medication that prevents HIV infection from sex or injection drug use.

That’s where Black churches come in.“Historically, the Black church has been a conduit for everything in Black families,” said Tony Yarber, former mayor of Jackson, Mississippi and pastor of the Relevant Empowerment Church. That influence can be a double edged sword. “The Black church is partially responsible for why Black folks have been averse to testing and the type of lifestyle changes necessary to prevent the spread of HIV. It makes sense that the pulpit is being used to spread the word of the importance of testing and how that and treatment works.”

Nunn started in Philadelphia, linking Mayor Michael Nutter’s Office of Faith Based Initiatives to pastors of Black churches around the importance of using their role and influence to reduce the high rates of HIV in the city.