Loucks studies cardiovascular health, an interest he traces back to his youth in British Columbia. By 18, he was a highly ranked triathlete. “I really got to know my body because I had to monitor it during those two-and-a-half-hour races,” he says. Later, with a degree in cardiovascular physiology under his belt, he was working toward a doctorate in pharmacology and therapeutics when he asked himself, What does the world need? “The world definitely needed help with cardiovascular disease,” he says. “It was and is the number-one cause of death. I really wanted to do something about it.”

Loucks began to study the biological mechanisms of how social factors such as poverty, abuse, or neglect affect health—especially cardiovascular health. At the same time, he maintained the serious mindfulness practice he’d begun at the age of 23. Then, a decade ago, the two came together.

In 2011, he and his colleagues added a mindfulness questionnaire to an NIH study they were working on, and were the first to discover that participants with the lowest levels of mindfulness—in other words, who were less aware of their thoughts and feelings—had more belly fat and worse regulation of their blood glucose, and were more likely to smoke and less likely to exercise than those who were naturally mindful.

As an MBSR-certified instructor himself, Loucks decided to tailor a mindfulness program for people with hypertension, focusing each session on a behavior that leads to high blood pressure. The results of the year-long study, published in 2019 and recently featured in The New York Times, showed that people who went through the customized program, dubbed Mindfulness-Based Blood Pressure Reduction, or MB-BP, significantly lowered their blood pressure readings. A follow-up study is currently under way, this time with a randomly assigned control group whose members will receive physician consultations and an at-home blood-pressure monitor rather than MB-BP. The addition of a control group will make it possible to determine whether it is in fact the mindfulness training that produces the improved health outcomes. The results are expected in August.

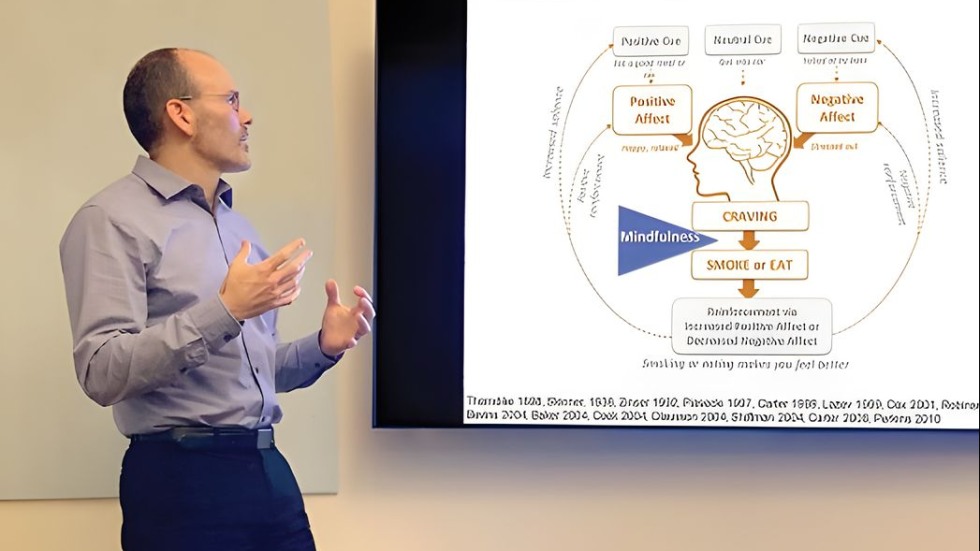

At the same time, Loucks and colleagues are working on the second phase of the five-year, $4.7 million NIH grant related to mindfulness and healthy habits. In the first phase, Willoughby Britton, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior and of behavioral and social sciences, Jared Lindahl, Ph.D., visiting assistant professor of religious studies, and Loucks scrutinized the data from studies involving thousands of participants to determine whether MBIs can be used to help patients stick to health-promoting lifestyle changes recommended by their doctors—and if so, what the “active ingredients” in mindfulness are that helped them do that. Evidence suggested that self-compassion and negative self-related rumination are two potentially important mechanisms.

In the second phase, Loucks and teams at Brown, Harvard University, and the University of Massachusetts are using their findings to customize two randomized controlled trials—the gold standard of clinical trials—that will look at the effect of MBIs on key health indicators such as blood pressure, mood, and medication adherence, all of which have significant effects on mental and physical health outcomes.

Loucks also heads the Mindfulness and Cardiovascular Lab, and is working with the lab’s coordinators, William Nardi ScM’19 and Frances Saadeh ’06 MPH’11, to create an MBSR-based program for “emerging adults”—also known as college students. This population, Loucks points out, is at a particularly unstable time of life. Mindfulness Based-College, or MB-College, is a nine-week course that focuses on age-relevant health issues such as diet, physical activity, and sleep and involves peer-to-peer interactions. They recently completed the first randomized controlled trial at Brown, and the results are promising. The study revealed that as the semester progressed, stressors increased but students’ depression levels remained stable; even better, loneliness levels dropped sharply over time because, Loucks says, “students were connecting with each other and having meaningful conversations” as part of the program. The contemplative practices baked into MB-College teach students “how they can be right here, right now for this life.” A second MB-College trial is now under way at Rhode Island College, a commuter college with a more socioeconomically diverse population and many first-generation college students.

Loucks recently received a grant to establish a network of researchers focused on using mindfulness to reverse the effects of early life adversity—what he calls “healing the past in the present moment”—and hopes to begin another, analyzing MBSR and its effects on pain, anxiety, and depression.