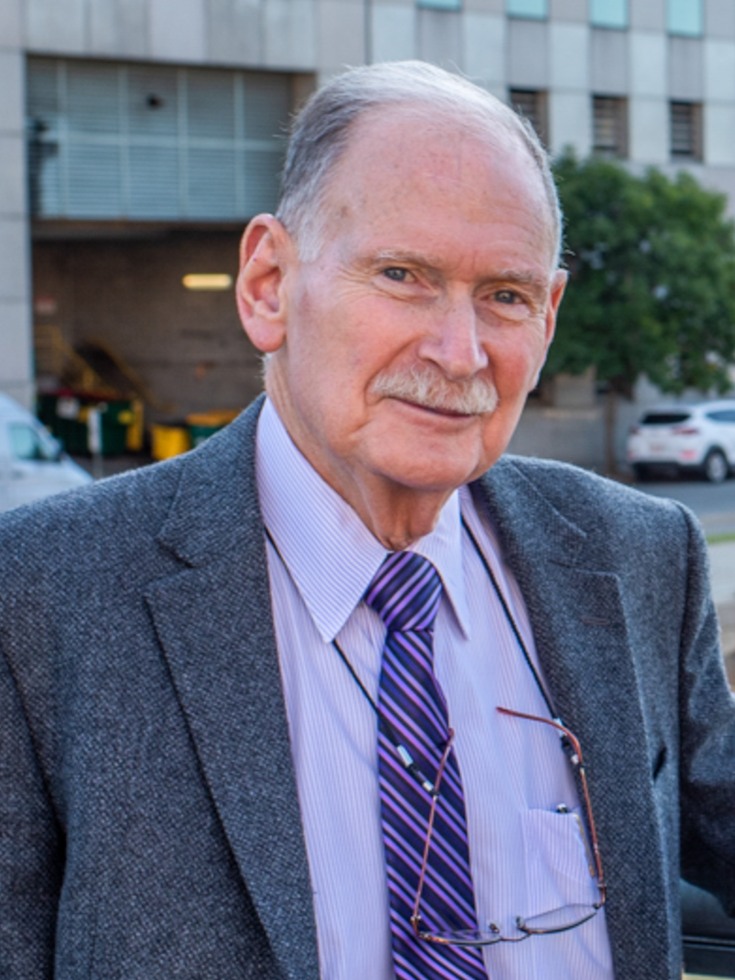

After an over 50-year career and nearly two decades at Brown, Dr. Richard Besdine decided to hand off leadership of the Center for Gerontology. While he continues to teach, mentor, and conduct research, Besdine considers his most important job “to help the people who succeed me to be even more successful.”

His successor, appointed in September of 2019, is Theresa Shireman, Ph.D., MS, professor of health services, policy and practice. Shireman, who came to Brown in 2015, specializes in pharmaco-epidemiology and health economic evaluations. She has been an active member of the School’s faculty, serving in leadership positions, teaching graduate courses, mentoring clinician scientists and doctoral students, and advancing the School’s commitment to diversity and inclusion. Shireman has managed numerous contracts with the State Medicaid agencies and contributes to NIH funded research evaluating pharmaceutical use in vulnerable

populations.

As the center’s new director, she sees its direction moving from policy evaluation, toward a more proactive approach to improving care. “Much of the work we’ve all done has been looking at things that have already happened and identifying problems, but less about trying to solve them,” Shireman said. “I see the center interested in trying to fix things, rather than just evaluate them.

“I think we’ll have much more primary data collection,” she said about the center’s future, “much more primary research, much more intervention-focused research.” There is even discussion of a living laboratory where observations can be made, and data collected, analyzed, and responded to in real time.

As an example, she points to the recent National Institute on Aging grant, led by Professor Mor, which will create a massive collaborative research incubator to develop trials aimed at evaluating interventions for patients with dementia. The research incubator, called the Imbedded Pragmatic AD/ADRD Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory, will fund and provide expert assistance to up to 40 pilot trials that will test non-drug, care-based interventions for people living with dementia, and develop best practices for implementing and evaluating interventions for Alzheimer’s and dementia care and share them with the research community at large.

In her new role, and with the coming “aging avalanche,” Shireman also sees a need for the center to focus on those who are not yet elderly. “We need to focus on people 50-60 years of age,” she said. “They are the bullwhip that’s going to come through and hit the system. We’re going to try to change their trajectories, to understand how and what resources are needed to keep people in their homes. It’s not just about their health, it’s about income inequality, it’s about the health of their communities.”

Explore:

Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research