America has a drinking problem. Between 2001 and 2013, the prevalence of high-risk drinking—defined as five or more alcoholic drinks in one sitting for men, and four or more for women—rose by roughly 30%. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic saw alcohol sales jump by nearly 3%, the largest increase in more than 50 years, and multiple studies suggest that about 25% of people drank more than usual during the pandemic. The problem is particularly acute among 18-29 year-olds, who lead the country in alcohol consumption levels.

Heavy drinking is associated with well-known health consequences, including absenteeism from work or school, reckless social behaviors and accidental injuries. Over the long-term, it contributes to heart and liver disease, mental health disorders, several forms of cancer and a number of other chronic conditions.

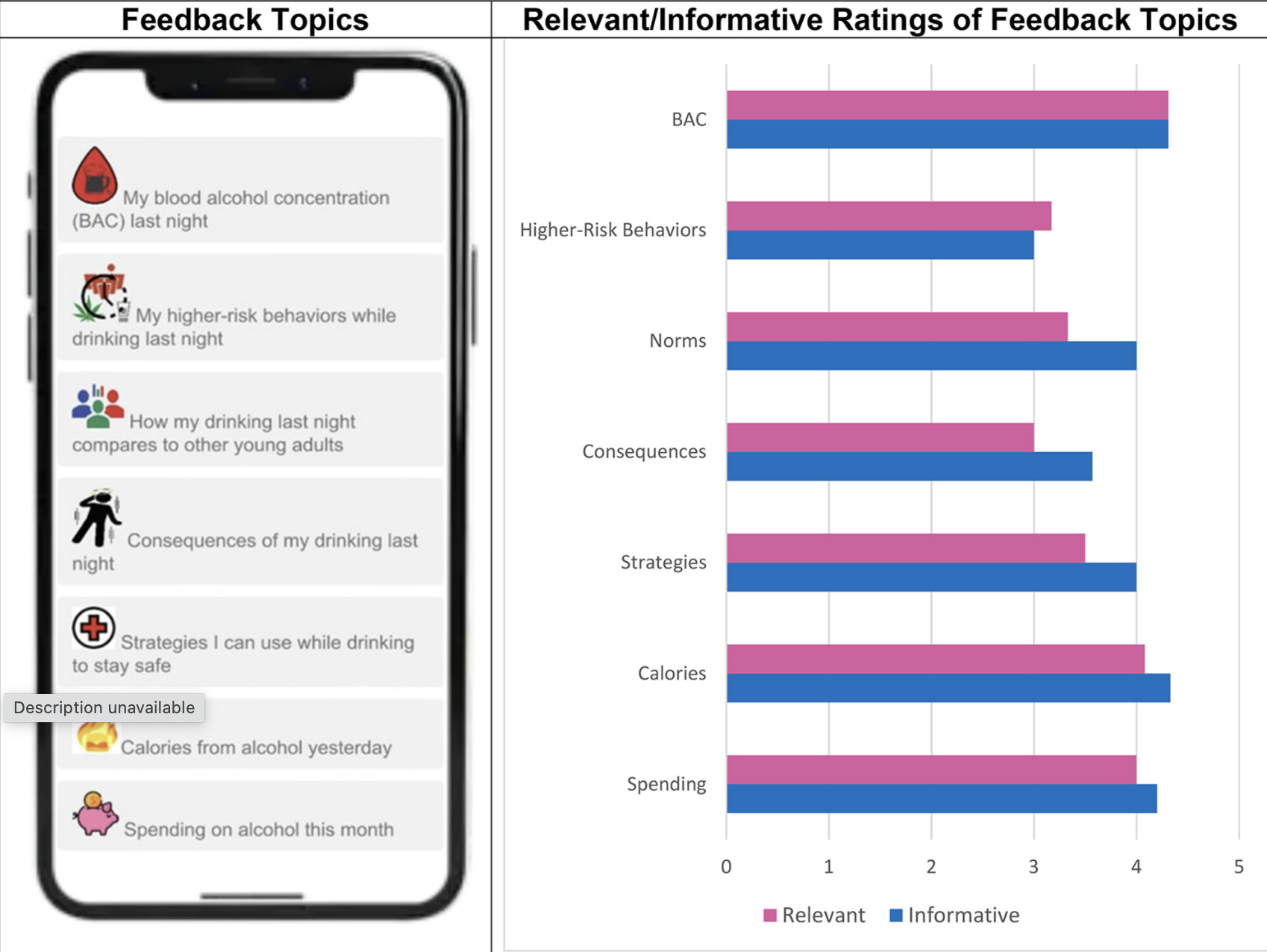

A team of researchers led by Jennifer Merrill, an associate professor of behavioral and social sciences at Brown, has developed a mobile app aimed at curbing drinking among young adults. The app—called Alcohol, Reflection and Morning Evaluation or A-FRAME—offers concise personalized feedback to help users reflect on their drinking and work towards healthier lifestyle goals.