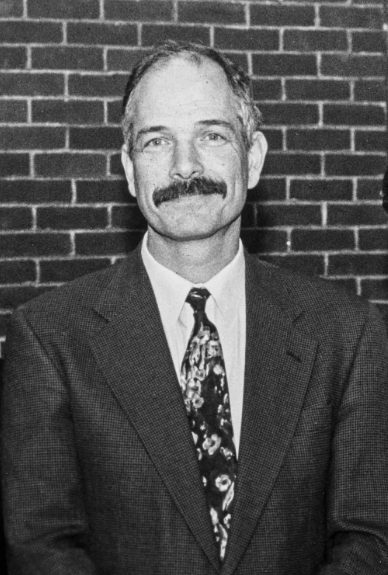

As our School of Public Health celebrates its ten-year anniversary, there is no one better able to tell the story of its founding than Professor Vincent Mor, who first conceived the idea for a school of public health at Brown. It was Mor, who arrived at Brown over 40 years ago, who persuaded the school’s inaugural dean, Terrie “Fox” Wetle, not only to come to Brown, but to see through his vision for a unified school of public health.

Mor arrived at Brown in 1981 as an assistant professor in what was then the Department of Community Health. At the time, the Department of Community Health, as well as all public health research at Brown, was housed in the University’s Division of Biology and Medicine. From 1996 to 2010, Mor served as the fifth and last chair of that department, helping to build the infrastructure for what would eventually serve as the foundation for the School of Public Health.

A longtime advocate for vulnerable elders, Mor directed the Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research at Brown for 10 years, one of Brown’s oldest and most prestigious public health research units. He has been principal investigator of more than 40 National Institutes of Health-funded grants focused on the uses and outcomes of health services by frail and chronically ill people. He is currently co-leader of a collaborative research incubator to support trials across the nation aimed at improving care for people living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. A member of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, in 2021 Mor was awarded the Rosenberger Medal of Honor, the highest honor the Brown University faculty can bestow.

We spoke with Professor Mor, who currently holds the appointment of Florence Pirce Grant University Professor of Health Services, Policy and Practice at Brown, about his early days at the University, his important contributions to hospice care, the major impact he says dementia will have on society, and the joy he’s gotten from training public health scholars.

Tell us what initially brought you to Brown over 40 years ago.

I've been at Brown since 1980, but officially since April of ‘81. I knew Brown’s associate dean of medicine at the time, Dr. David Greer, through work at a Harvard-related hospital in Boston, and we had relationships with the Brown University Medical School. I’d worked with the State Department of Health and Human Services on a variety of different projects in the mid ‘70s, and then a big request for applications came out to do a national evaluation of the potential for a hospice benefit, which did not then exist. So my team and I bid on this, together with Brown’s School of Medicine, and it was funded in October of 1980.

For six months I commuted to Providence. Then I set up a team to work on that project, and that team evolved into a research unit, and then in about 1982 or ‘83, it began to fuse with what had become one of the first centers in the School of Medicine focused on research, the Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research.

That was the reason I came to Brown, and then other grants came from that effort as well. So it was a natural process and a great opportunity for me. I was appointed in the Department of Community Health, which was one of the original departments in the medical school and already had a linkage to the undergraduate program through an undergraduate concentration that had developed very early.

Others have described this early period of the medical school as a special time at Brown.

When I arrived at Brown, the medical school was only 8 years old. It was a combination of Brown’s biology departments, together with the hospitals and the academic clinical faculty—so it was tabula rasa. It was the opportunity to paint something completely different.

There was a major initiative in alcohol and addiction studies underway at the time. David Lewis, its founder, led a clinical research program which also had a large training component for physicians, as well as taking advantage of the existing, very strong psychology internship program within the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior.

So all the pieces were there. The leavening was essentially the entrepreneurial spirit that Dean David Greer fed and nourished. And in some sense, he gave us, not carte blanche, but he said, go out and do stuff, and we did. That entrepreneurial spirit of grant-fed research was very important.