Early studies into MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD have been so impressive as to be startling: “Placebo-controlled study of participants with treatment-resistant PTSD showed that 85% of those in the MDMA study (compared with 15% in the placebo group) no longer had a diagnosis of PTSD after three sessions of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy,” write Ben Sessa and David Nutt for the British Journal of Psychiatry. “And the results were sustained at 3.5 years long-term follow-up.”

“The results so far have been amazing,” says Eaton. “This is far and away much greater efficacy than meds and psychotherapy. And then there’s the longevity of those effects. We just do not see that sort of effectiveness elsewhere or with other treatments.”

Capone adds: “And this occurs with only one course of treatment. The patients are not on daily meds. And they continue to get better. It’s quite different from anything we’ve seen before. We’re looking at brain changes. The process continues after they’ve finished with the treatment.”

With conventional therapies, says Capone, “patients leave the VA and, very often, come right back. The treatment doesn’t stick and there’s a high dropout rate. Many patients were coming through the program and not benefitting. MDMA is like night and day.”

Heeding the Science

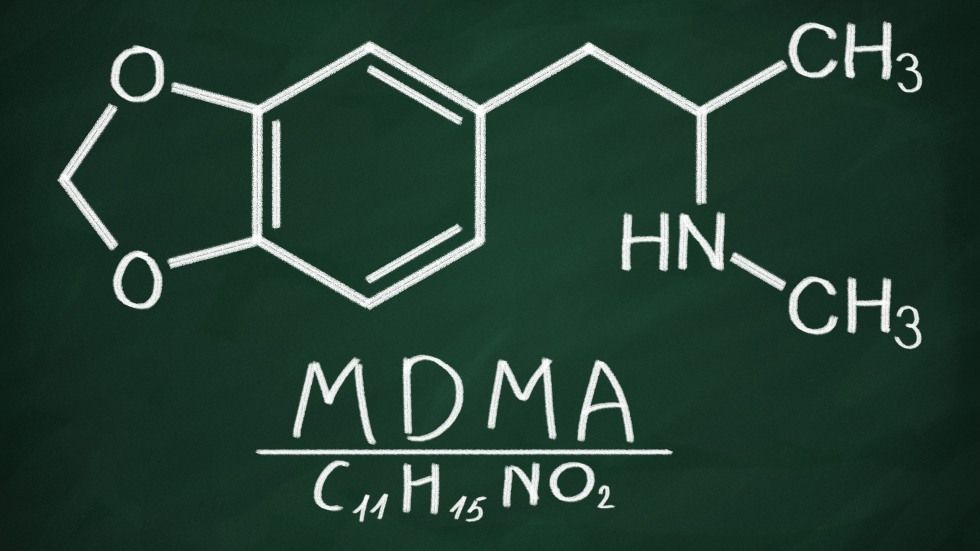

How does MDMA-assisted therapy produce these results? There are a few hypotheses. One is that MDMA reduces inflammation in the brain caused by PTSD. Researchers also posit that it “improves bonding and raises levels of empathy, empathetic understanding, and compassionate regard.” Professors Eaton, Capone, and Haass-Koffler write that the “combined neurobiological effects of MDMA increase compassion, reduce defenses and fear of emotional injury, and enhance communication and introspection.”

“Essentially what it can do is increase the brain’s ability to hold more serotonin,” Eaton said, “and it seems as though that can be the driving force. It also increases oxytocin, which is known as the caregiving or love hormone. And we think that is a really important aspect of the assisted therapy part of the program and why it can be so impactful; because the trust between the participant and the therapist allows for the space for these changes to occur.”

There is a caveat: “There has been much news around psychedelics over the last several years,” says Eaton. “There is some well-earned enthusiasm, but we should remain cautious. Private companies want to capitalize on this. It’s a little worrisome. Some will try to use this as a moneymaker without trying to do it justice. We’re hoping that the profit-motive doesn’t outpace the science.”

First Steps

Brown’s pilot study will officially begin in February 2023. It is the first step in creating a body of work and infrastructure around the issue. The larger plan is to form a center for psychedelics research at the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies (CAAS).

The clinical team conducting the study is composed of four certified therapists who are currently training with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which is one of the working bodies sponsoring trials to investigate the efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapy on veterans with PTSD. MAPS spearheads negotiations with the FDA and supports the study at Brown.

“It’s a big undertaking for therapists and participants alike to go through 15 therapy sessions,” says Eaton, “and then two eight-hour-long sessions of MDMA treatment. It’s also resource intensive as therapists work in pairs during those two full days when MDMA is administered.”

In addition to the Providence VA, MAPS, CADRE, and CAAS, the study involves the Warren Alpert Medical School.

“We’re excited about forming this great collaboration with Dr. Haass-Koffler, who has her own expertise in pharmacokinetics and biomarkers,” says Eaton. We’re building a really good team and looking into what we can explore further.”

“I think we feel such an urgency to explore other treatment options,” says Capone, “not just because veterans don’t get much better under the conventional protocols, but because some of them are dying or have died under our watch. That really drives us forward to explore MDMA therapy.”

“It’s a real crisis among our veterans and the mental health system in general,” says Eaton. “To have a program that puts people in a better place—and to be able to lower the suicide rate—is frankly magic and a real beautiful thing to be a part of.”